- Home

- Captain W E Johns

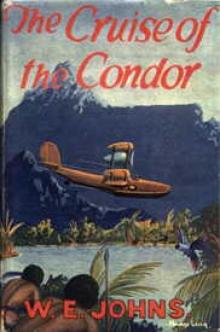

Biggles In The Cruise Of The Condor (02) Page 6

Biggles In The Cruise Of The Condor (02) Read online

Page 6

"Sounded like magneto to me, sir, the way she cut out so sudden like," observed Smyth, climbing into the cockpit and then out on to the hull behind the engine. "I shall have to wait a minute or two to let her cool down before I can do anything," he added.

"Well, there doesn't appear to be any particular hurry," said Biggles. "We were lucky she cut out where she did and not somewhere over the forest or one of those places where the river wound about so much. Have a look at her, Smyth, and tell me if you want any help."

For a quarter of an hour or twenty minutes Smyth laboured at the engine, the others watching him with interest. "It's the mag, as I thought," remarked the mechanic; "brush has gone. I've a spare inside."

In a few minutes the faulty part was replaced and the cause of the breakdown remedied. As Smyth reached for the magneto cover, and a spanner to bolt it on, Biggles turned away casually to return to his cockpit, but the next moment a shrill cry of alarm broke from his lips as he pointed to the bank, past which they were floating with everincreasing speed.

"We've drifted to the head of some rapids," said Dickpa crisply. "Get the engines started; we've no time to lose."

An eddy caught the nose of the Condor and spun the machine round in its own length. They swung dizzily round a bend, and as the new vista came into view a cry of horror broke from Algy, and he pointed, white-faced. High in the air, not a quarter of a mile away, hung a great white cloud. A low rumble, like the roll of distant thunder rapidly approaching, reached the ears of the listeners.

"The falls!" cried Biggles. "The falls! Get that mag jacket on, Smyth, for heaven's sake; if it isn't on in two minutes we're lost."

The current had now seized the machine in its relentless grip and was whirling it along at terrific speed: from time to time an eddy would swing it round dizzily, a manoeuvre the pilot had no means of checking.

"Look out!" Algy, taking his life in his hands, reached far over the side and fended the Condor away from a jagged point of rock that thrust a black, toothlike spur above the surface. By his presence of mind the danger was averted almost before it had arisen, but little flecks of foam marked the positions of more 'ahead. Straight across their path lay_ a long, black

boulder; a miniature island around which the water seethed and raged in white, lashed fury.

"If we hit that we're sunk," snapped Biggles. "How long will you be, Smyth?"

"One minute, sir."

"That's thirty seconds too long," replied Biggles, and the truth of his words was only too apparent to the others, for the Condor was literally racing towards the rock as if determined to destroy herself. A bare hundred yards beyond it the river ended abruptly where it plunged out of sight into the mighty seething cauldron below. The rock seemed literally to leap towards them.

"Steady, Algy! Leave me if I don't make the bank," barked Biggles, and, before the others could realise his intentions, he had seized a mooring-rope and taken a flying leap onto the rock. He landed on his feet and flung his weight against the nose of the machine. Waterborne, it swung away swiftly. The tail whipped round, the elevators literally grazing the rock, and the next instant it was clear. Biggles took a lightning turn of the rope round a jutting piece of rock and flung himself backwards to take the strain. The rope jerked taut with a twang like a great banjo-string, and the Condor, nose towards the rock, remained motionless, two curling feathers of spray leaping up from her bow as it cut the raging torrent. Algy, in the cockpit, was pressing the self-starter furiously, and looked up as the engines came to life. He opened the throttles, and the machine began to surge slowly towards the rock. For a minute Biggles watched it uncomprehendingly. The rope was slack and the engines were roaring on full throttle, yet the Condor was making little or no headway. It seemed absurd, but as the truth became obvious his heart grew cold with horror. Slowly the full significance of what was happening dawned upon him. He realised that against the rapids it was an utter impossibility for the machine to make sufficient headway to get enough flying speed to lift it. They were in the middle of the stream, and to attempt to reach either bank meant they would inevitably go sideways over the falls before they could reach it. Only one path remained—

downstream—and that way lay the falls. For a moment or two Biggles did not even consider it, but then, as he saw it was the only way they could go unless they intended to remain for ever as they were, he began to weigh up the chances. There was no wind. The current was running at perhaps thirty or forty miles an hour, and that would consequently be the Condor's speed the instant she was released. Another twenty or thirty miles an hour on top of that and they would be travelling at nearly seventy miles an hour, which was ample for a takeoff. The only doubt in his mind was whether or not she would "unstick". He knew, of course, that nearly all marine craft were slow to leave the water unless they got a "kick" from a wave or the assistance of broken water. That was a risk he would have to take, he decide&

The Condor, still under full throttle, had nearly nosed up to the rock now, and Biggles saw that Algy was shouting. He could not hear what he said for the noise of the engines and the rushing water, but he could guess by his actions what he was trying to convey. Algy was trying to tell him that the machine could not get sufficient flying speed to rise against such a current. "I know that," thought Biggles grimly as he examined the course he would have to take as he went downstream. There were several rocks projecting above the water, but fortunately none in a direct line between him and the falls. The Condor was just holding its own against the current, travelling so slowly that it would require far more petrol than they had on board for it ever to get above the rapids. Biggles made up his mind suddenly, and sprang like a cat for the nose of the machine. He jerked down into his seat while Algy stared at him with ashen face. Biggles motioned him into his seat, reached over, cut the rope, and then kicked the rudder hard over. The Condor bucked like a wild horse as the stream caught her, and the next instant they were tearing through a sea of spray towards apparent destruction. Eighty yards—seventy—sixty—Biggles bit his lip. Would she never lift? The combined noise of the engines and the falls was devastating, yet the pilot did not swerve an inch. Thirty yards from the bank he glanced at his air speed indicator, and then jerked the stick back into his stomach. The machine lifted, hung for a moment as if undecided as to whether to go on or fall back on the water again, then picked up and plunged into the opaque cloud of spray.

The pilot's heart missed a beat as they rocked and dropped like a stone in the terrific " bump", or down-current, caused by the cold, moisture-soaked atmosphere. The engines spluttered, missed fire, picked up again, missed, and Biggles thought the end had come. He knew only too well the cause of the trouble; the spray was pouring into the air intake and choking his engines.

The Condor burst out into the sunshine on the other side of the cloud, the engines picked up with a shrill crescendo bellow, and the machine soared upwards like a bird. Out of the corner of his eye Biggles caught a glimpse of the rock-torn maelstrom below, and leaned back limply in his cockpit. He caught Algy's eye and shook his head weakly, as if the matter was beyond words. Algy gave him a sickly grin and disappeared into the cabin, to allow Dickpa to resume his seat in the cockpit in order to point out the way. Dickpa leaned towards him. "I thought you said this was, the safest form of transport in the world!" he bellowed sarcastically.

"Quite right," yelled Biggles. "Where would you have been in a canoe?" Dickpa shook his head with a wry face and turned his attention to the ground below. They had already passed the place where they had come down on the water and were nearing the open prairies ahead. Tall trees, chiefly burity palms, and thick vegetation lined the river-banks, but Biggles saw several places where a landing might be safely attempted. Mountain ranges appeared at several points in the distance, their blue tints, caused by the clear atmosphere, giving way to a dull red colour as they drew nearer. Biggles was amazed at the grotesque formation of the rocks. Against the skyline they often looked, as Dickpa had said, like

mighty frowning castles, complete with battlements and turrets, but at close quarters the resemblance was lost in a maze of pinnacles, gaunt, stark, and utterly desolate. He was staring at a startling pile of rocks, blood-red with yellow ochre streaks, when Dickpa touched him on the arm and pointed downwards. Biggles looked, and saw that in one or two places where the river skirted the foot of the mountains it widened out into a sort of lagoon. Turning, he raised his eyebrows inquiringly, and, in answer to Dickpa's signal, throttled back and began a long spiral glide towards the largest stretch of water. The landing presented no difficulties, and the Condor soon ran to a standstill on the smooth water. Biggles taxied up to the bank, switched off, and, as the engines fitfully spluttered to silence, raised himself stiffly and looked around."

"Well, here we are," said Dickpa brightly. "I think this is the safest place where we could land within striking distance of the actual spot for which we are bound. It is still a little distance away, but within walking distance, so there seemed to be no need to risk a landing on hard ground."

Biggles surveyed the place with interest. Seen from 'water-level, they appeared to be on a lake, enclosed on three sides by a wall of dark-green foliage, and on the other side by an awe-inspiring mass of rock that rose, tier by tier, far into the blue sky above. This was the side towards which Biggles had taxied, for a narrow strip of shelving sand fringed the river and formed a small beach on which they could step ashore. Near at hand a mass of exotic flowers overran some low bushes and fell in a vivid scarlet cascade to the very edge of the water. A humming-bird darted towards the Condor, hung poised for a moment on vibrating wings, and then flashed like a living jewel towards the flowers. A flight of blue-and-orange macaws passed overhead, uttering harsh metallic cries and Biggles turned towards Dickpa with an appreciative smile.

"Nice spot," he observed cheerfully.

"It looks like it," agreed Dickpa quietly, "but things are not always what they seem in this part of the world. Take a look at that fellow, for instance," he added, pointing. The others followed the finger with their eyes, and were just in time to see a long, dark shadow glide into the water.

"What a horror!" muttered Biggles, with a shudder.

"Anaconda—quite harmless," returned Dickpa calmly. "It's the fellows that do the damage. Comparatively few snakes are venomous, really deadly, but it takes some time to learn which they are. The safest thing is to keep clear of all of them."

"You needn't tell me that," replied Biggles warmly. "I shan't worry them if they don't worry me. What is our plan now?" he inquired, changing the subject.

"I don't think we can do better than make camp here," answered Dickpa. "We'll moor the machine securely, so that she can't drift away, and then get some stores out. We'll go on foot to the treasure-cave tomorrow. It's only a few miles away, but I'm afraid it's too late for us to start today; this is no place to be benighted, as you may learn before we're finished."

"That suits me," agreed Biggles. "Smyth had better have a good look over the machine. There isn't very much to do here; don't you think it would be a good idea if I took a stroll along the river-bank and made a rough survey for shoals or rocks, in case there are any about? We might have to take off in a hurry, and it's as well to be on the safe side."

"Very wise," replied Dickpa at once. "There might be an old tree-trunk or two on the water, and we don't want to hit anything like that, I imagine."

"We certainly do not," returned Biggles emphatically.

"All right, you take a look around while Algy and I get the hammocks ashore. By the way, I should take a gun with you."

"I'm not likely to go without one," grinned Biggles. "I haven't forgotten the gentleman we just saw slithering into the water."

"Oh, he won't worry you, but mind you don't step on a croc, and don't eat any fruit without showing it to me first," was Dickpa's final warning as Biggles, with a rifle under his arm, set off up the river.

CHAPTER VIII

INDIANS

WHILE the beach lasted, Biggles found the going easy, but he advanced cautiously, keeping a watchful eye on the bushes that skirted the foot of the cliff; presently large boulders and rocks that had fallen from above obstructed his path, and progress became slower. From time to time he climbed up to the top of these and examined the surface of the water critically; he was soon glad that he had taken the precaution, for in many places he could see great masses of dark rock just below the surface which would have crushed the bottom of the Condor like an eggshell had the amphibian come in contact with them when taking off.

The position of these he tried to memorise, and, to make doubly sure, he marked them down on a rough sketch-map. From time to time he could still see the machine, with its nose almost touching the beach, and the others carrying things from it to the shore, but now the bank curved inwards and hid them from view. A swarm of insects began to collect above him, and he struck savagely at the bees that settled and clung persistently to his face. "What a curse you are!" he growled as he quickly discovered that his efforts went unrewarded.

The sun, now past its zenith, was blazing hot, and the going became still more difficult. Great trees, festooned with lianas, began to crowd down to the water's edge, and he advanced more warily. Once a butterfly, with wings as large as the palms of his hands, brought his heart into his mouth as it darted within a foot of his face in swift, bird-like flight.

In the shade of the trees the heat was even more oppressive, and the silence uncanny. When he stood still he could hear furtive rustlings among the dead leaves at his feet and all around him, and these, he ascertained by careful investigation, were caused by ants as they toiled indefatigably at innumerable tasks. Once he halted to watch an incredible army of them passing by, marching steadily in a long, winding column that disappeared into the dim recesses of the jungle.

Turning another corner, he pulled up dead in his tracks and slowly brought his rifle to the ready. Straight in front of him, near the water's edge, and not fifty yards away, was a palm-thatched shack in the last stages of dilapidation. Near it was a canoe, also very much the worse for wear, with a paddle lying across it.

"Anyone at home?" he called loudly.

All remained silent except for the buzzing of the countless insects. He approached warily. "Anyone at home?" he called again, eyeing the canoe suspiciously. "If the occupant is not inside, how has he departed without his canoe, his only means of transport?" he mused. As he drew closer he saw that a tangle of weeds had sprung up inside the boat, and it was evident that it had not been moved for some time. With a grim suspicion already half formed in his mind, he was not altogether surprised at what he saw when he pushed the ramshackle door open.

A cloud of flies arose with a loud buzz from an object that lay upon a rough mattress in a corner of the room. He walked slowly over to it, and then turned quickly away. Upon the primitive bed lay what had once been the body of a man—a negro, judging by the short, curly black hair. An old-fashioned muzzle-loading rifle lay beside him, and near it a glass bottle that had once, according to the label, contained quinine, told its own story. On the far side of the room were a number of rough, round, smoke-blackened balls, about the size

of footballs, the product of nature to collect which the man had sacrificed his life. Biggles knew without examining them closer that they were rubber—the crude, heatsolidified latex of the tree that gave it its name. The gruesome tragedy was plain enough to see. The man had been a rubber collector, and, overtaken with the inevitable fever, had taken to his bed, where, far from the help of others of his kind, he had died a lonely and pitiful death.

Depressed by the sad spectacle, Biggles hastened out into the fresh air and looked moodily at the unfortunate man's equipment, and then, with a sigh, passed on, strangely moved by the silent drama of loneliness and death.

But he did not go far. Having achieved the object of his walk, he began to retrace his steps—slowly, for there were many things to interest him. Once it was a spray of orchids that

sprang from a rotten tree and which would have cost a small fortune in a London florist's. Sometimes it was a bird of unbelievable colours, or shoals of fish in the water. The sun was now low in the sky, and, realising that he had taken longer over his journey than the object of it justified, he quickened his steps.

He reached the beach and breathed a sigh of relief as his eyes picked out the amphibian still at its moorings. Why he was relieved he hardly knew, unless it was that the loneliness of the forest had depressed him. He could not see the others, but he did not worry on that score; no doubt they were lying in the shade, resting after their efforts. But as he approached and they still did not appear, an unaccountable fear assailed him, although he ridiculed himself for his alarm.

"Ahoy there!" he cried in a ringing, high-pitched voice that reflected his anxiety. There was no reply. The words had echoed to silence before he moved, and then he acted swiftly. He cocked his rifle and, after a quick, penetrating glance around, broke into a swerving

run towards the Condor. Reaching it, he pulled up in consternation at the sight that met his gaze.

The machine was apparently untouched, yet all around on the beach the sand was kicked up and ploughed in such a way as could only have been caused by a fierce struggle. "But what? What could they struggle with in such a place?" was the thought that hammered through his brain.

A fire was still smouldering on some stones, and the hammocks, looking as if they had been carelessly flung down, lay near it. Then his eye caught something on the machine that sent him hurrying towards it, ashen-faced. It was an arrow, feathered with scarlet macaw pinions.

Indians! So that was it. What had happened he could only guess, but for one thing he was thankful. There were no bodies on the beach, and this suggested that Dickpa and the others had been surprised and overpowered before they could reach the weapons in the machine.

"The Indians have got 'em, no doubt of that," he thought grimly. "Well, if I can't get them back they may as well have me too. The question is, which way have they gone?" It was easily answered, for an unmistakable track of bare feet led to a flaw in the rock which opened out into a distinct path. A few yards farther on he stooped and picked up a tiny white seed with a grunt of satisfaction. Presently he found another, and another. It was rice, and the solution flashed upon him at once.

Biggles in the Underworld

Biggles in the Underworld Biggles' Special Case

Biggles' Special Case 34 Biggles Hunts Big Game

34 Biggles Hunts Big Game 03 Now To The Stars

03 Now To The Stars 55 No Rest For Biggles

55 No Rest For Biggles 46 Biggles in the Gobi

46 Biggles in the Gobi 52 Biggles In Australia

52 Biggles In Australia 51 Biggles Pioneer Air Fighter

51 Biggles Pioneer Air Fighter 05 Biggles Flies East

05 Biggles Flies East 28 Biggles In Borneo

28 Biggles In Borneo 29 Biggles Fails to Return

29 Biggles Fails to Return 55 No Rest For Biggles (v2)

55 No Rest For Biggles (v2) Biggles Does Some Homework

Biggles Does Some Homework Biggles of the Camel Squadron

Biggles of the Camel Squadron 35 Biggles Takes A Holiday

35 Biggles Takes A Holiday Biggles And The Black Peril (06)

Biggles And The Black Peril (06) 17 Biggles And The Rescue Flight

17 Biggles And The Rescue Flight Biggles Learns To Fly

Biggles Learns To Fly 40 Biggles Works It Out

40 Biggles Works It Out 05 Biggles Learns To Fly

05 Biggles Learns To Fly 04 Gimlet Mops Up

04 Gimlet Mops Up 10 Biggles and Co

10 Biggles and Co 47 Biggles Of The Special Air Police

47 Biggles Of The Special Air Police Biggles and the Noble Lord

Biggles and the Noble Lord T2 Return To Mars

T2 Return To Mars 21 Biggles In the South Seas

21 Biggles In the South Seas No Rest For Biggles

No Rest For Biggles Biggles In The Cruise Of The Condor (02)

Biggles In The Cruise Of The Condor (02) 06 Biggles And The Black Peril

06 Biggles And The Black Peril Biggles and the Deep Blue Sea

Biggles and the Deep Blue Sea 06 Biggles Hits The Trail

06 Biggles Hits The Trail 39 Biggles Goes To School

39 Biggles Goes To School 44 Biggles and the Black Raider

44 Biggles and the Black Raider 42 Biggles Follows On

42 Biggles Follows On Biggles In the South Seas

Biggles In the South Seas 21 Biggles In The Baltic v3

21 Biggles In The Baltic v3 27 Biggles - Charter Pilot

27 Biggles - Charter Pilot 49 Biggles Cuts It Fine

49 Biggles Cuts It Fine 51 Biggles Foreign Legionaire

51 Biggles Foreign Legionaire 04 Biggles Flies Again

04 Biggles Flies Again 16 Biggles Flies North

16 Biggles Flies North 37 Biggles Gets His Men

37 Biggles Gets His Men 07 Gimlet Bores In

07 Gimlet Bores In 19 Biggles Secret Agent

19 Biggles Secret Agent 32 Biggles In The Orient

32 Biggles In The Orient Adventure Unlimited

Adventure Unlimited 26 Biggles Sweeps The Desert

26 Biggles Sweeps The Desert Biggles Air Detective (43)

Biggles Air Detective (43) 36 Biggles Breaks The Silence

36 Biggles Breaks The Silence 14 Biggles Goes To War

14 Biggles Goes To War 18 Biggles In Spain

18 Biggles In Spain 50 Biggles and the Pirate Treasure

50 Biggles and the Pirate Treasure 25 Biggles In The Jungle

25 Biggles In The Jungle 23 Biggles Sees It Through

23 Biggles Sees It Through 21 Biggles In The Baltic

21 Biggles In The Baltic 24 Spitfire Parade

24 Spitfire Parade 38 Another Job For Biggles

38 Another Job For Biggles 41 Biggles Takes The Case

41 Biggles Takes The Case 43 Biggles Air Detective

43 Biggles Air Detective 53 Biggles Chinese Puzzle

53 Biggles Chinese Puzzle Biggles Pioneer Air Fighter (51)

Biggles Pioneer Air Fighter (51) 22 Biggles Defies The Swastika

22 Biggles Defies The Swastika 01 Kings Of Space

01 Kings Of Space